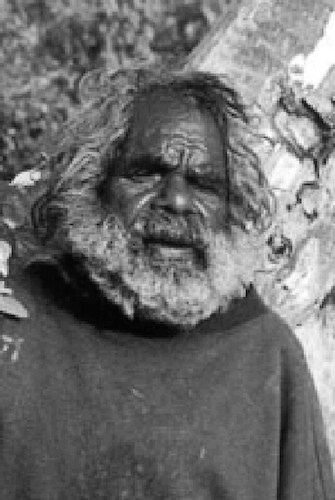

Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula

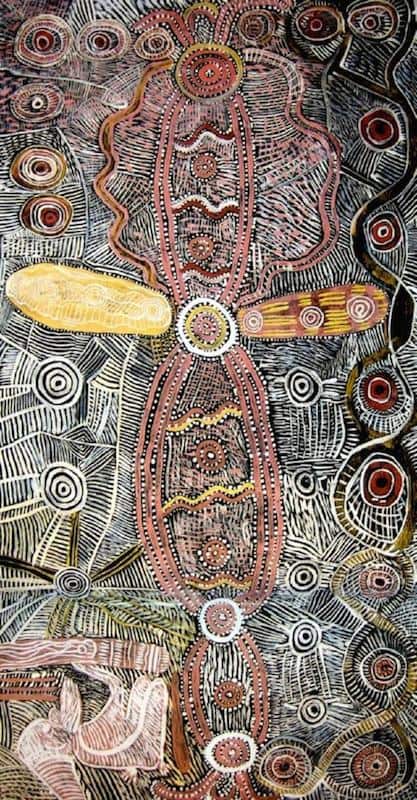

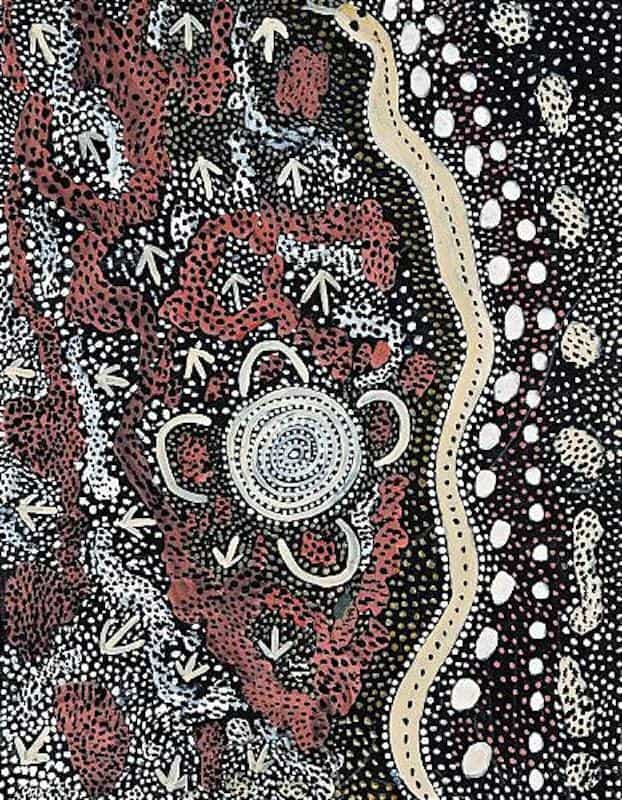

Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula was one of the founding members of the Western desert Aboriginal art movement. He was an extremely innovative artist who depicted traditional ceremonial ground designs as abstract depictions on Canvass and board. He had a distinctive style characterized by layering and over-dotting. His art depicted the myths and journeys associated with the sacred waterhole at Ilpilli.

Many of his early works are spiritual and contain secret imagery meant only for the eyes of initiated men. His later works are on Canvass but maintain a very high standard.

His best paintings reverberate with the power of ancient knowledge and forms while captivating western audiences through his uncanny ability to access to our modern sensibilities.

The aim of this article is to assist readers in identifying if their Aboriginal painting is by Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula. It compares examples of his work. It also gives some background to the life of this fascinating artist.

If you have a Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula Aboriginal painting to sell please contact me. If you want to know what your Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula painting is worth please feel free to send me a Jpeg. I would love to see it.

Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula early Life

Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula was born 1925 at Mintjilpirri, north-west of the Kangaroo Dreaming site of Ilpili waterhole. His family first met white people when he was 12. By the age of 15, he and his family moved into Hermannsburg mission.

Warungula went through traditional initiation ceremonies just outside the mission. As a young man, he worked on roads and airstrips at Hermannsburg. His road work also led him to travel to Haasts Bluff, and Mount Wedge during the 1950’s. He moved into Papunya with his first wife in the 1960’s. By the early 1970’s like Long Jack and Mick Tjapaltjarri, he was a Papunya settlement counselor.

Early painting

In 1971 Geoff Bardon became a local school teacher at Papunya primary. He tried to encourage local children to paint in their own traditional style. When Bardon was told only older men could paint these stories he to started a men’s painting group.

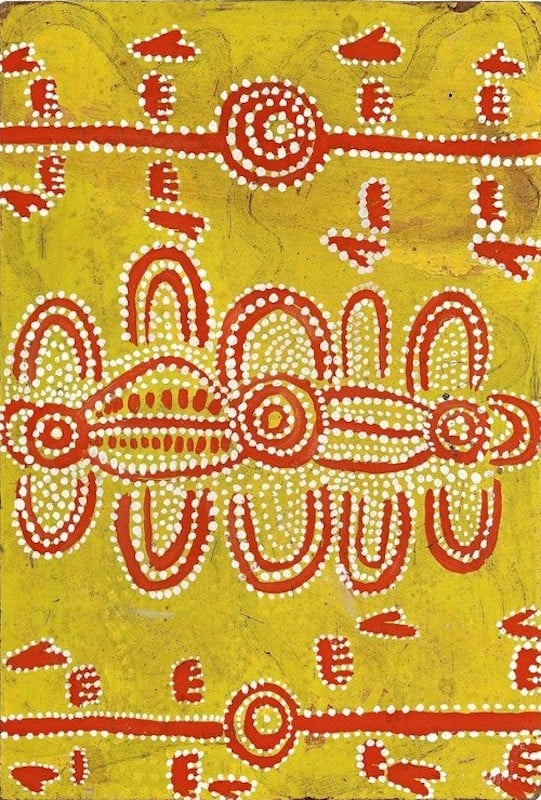

Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula was one of these early western desert painters. The painters’ group would congregate after work and discuss their stories and experiment artistically. From the outset, he emerged as an innovative and prolific artist. These early works are often quite small and done on composite boards and any other material available.

His early paintings radiate power from the tightly composed and intensely vibrant surfaces

From the outset of his career, Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula intuitively transformed traditional desert ceremonial ground designs into inventive paintings.

He was a custodian of the Kalipinya water dreaming which he shared with Old Walter and Long Jack.

Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula Middle Period

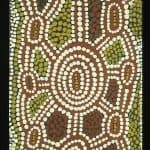

Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula quickly developed a distinctive style. His style was characterized by layering and over-dotting. Dots were initially used to hide and veil secret imagery. Johnny turned them into an integral part of his style. According to Bardon Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula was the first artist to used dotting as a background to his painting. This dot-dot style is now what is commonly recognized internationally as aboriginal art.

Bardon recognized his talent and encouraged his innovative style.

According to Bardon “Johnny was amongst the most inventive of the early Papunya artists. His ‘calligraphic line and smearing brushwork’ gave a relative solidity to the features of the land”…“often interspersed with animal tracks or symbolic figures woven in to tightly synchronized compositions that still resound with freshness and surprising spontaneity”.

In 1978 Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula painted a large canvas called Tingari men at Tjikarri. It was entered into and became a finalist in the Alice Art Prize. It was purchased and became a part of the Araluen Art Collection.

Later Life

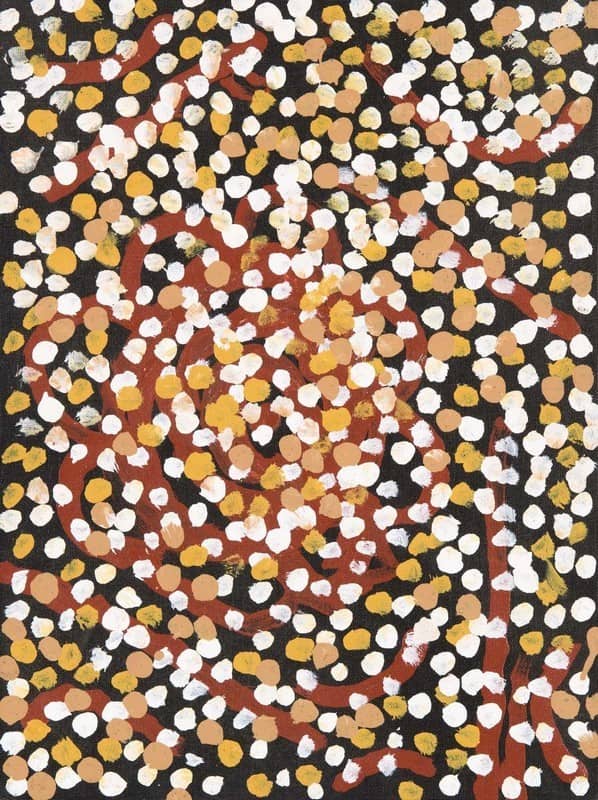

By the mid-1980’s Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula eyesight began to fail. His painting became infrequent and of poorer quality. By the end of the 1990’s Warangkula was old and infirm.

These later paintings are not popular with collectors and hold little value.

In the 1990’s he started painting again and produced hundreds of raw expressionistic paintings. These later paintings though were crude and paled compared to his earlier works.

He spent the last years of his life with his wife and children in Papunya. His greatest legacy is the simple but enigmatic dot dot background. It is so strongly associated with aboriginal art that it is now almost inseparable.

Warungula Tjupurrula name can also be spelled Warungula Djupurrula or Warungula Jupurrula. His Christian name was Johnny

Warungula Tjupurrula can be spelled, Warrangula or Warangkula

Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula references

Papunya Tula Art of the Western desert

Early Papunya Artworks and Articles

All images in this article are for educational purposes only.

This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which was not specified by the copyright owner.

Johnny Warungula Tjupurrula Images

The following images are not the complete known work by this artist but give a good idea of his style and range.